Mary Wells

Biography

Mary Esther Wells (May 13, 1943 – July 26, 1992) was an American singer who defined the early sound of Motown Records in the early sixties. Along with The Miracles, The Temptations, The Supremes, and The Four Tops, Wells was said to have been part of the charge in black music onto radio stations and record shelves of mainstream America "bridging the color lines in music at the time." With a string of hit singles mainly composed by Smokey Robinson including "Two Lovers" (1962), the Grammy-nomin...

Mary Esther Wells (May 13, 1943 – July 26, 1992) was an American singer who defined the early sound of Motown Records in the early sixties. Along with The Miracles, The Temptations, The Supremes, and The Four Tops, Wells was said to have been part of the charge in black music onto radio stations and record shelves of mainstream America "bridging the color lines in music at the time."

With a string of hit singles mainly composed by Smokey Robinson including "Two Lovers" (1962), the Grammy-nominated "You Beat Me to the Punch" (1962) and her signature hit, "My Guy" (1964), she became recognized as "The Queen of Motown" until her departure from the company in 1964, at the height of her popularity. In other circles, she's referred to as the "The First Lady of Motown" and was one of Motown's first singing superstars.

Mary Esther Wells was born near Detroit's Wayne State University on May 13, 1943 to a domestic mother and an absentee father. One of three children, she caught spinal meningitis at the age of two and struggled with partial blindness, deafness in one ear and temporary paralysis. During her early years, Wells' family grew up in a poor residential Detroit district. By age 12, Wells was helping her mother with housecleaning work. She described the ordeal years later:

"Daywork they called it, and it was damn cold on hallway linoleum. Misery is Detroit linoleum in January--with a half-froze bucket of Spic-and-Span."

Wells used singing as her comfort from her pain and by age ten had graduated from church choirs to performing at local nightclubs in the Detroit area. Wells graduated from Detroit's Northwestern High School at the age of 17 and set on sights of becoming a scientist but already hearing about the success of Detroit musicians such as Jackie Wilson and The Miracles decided to try her hand at music as a singer-songwriter.

In 1960, 17-year-old Wells approached Tamla Records founder Berry Gordy at Detroit's Twenty Grand club with a song she had intended for Jackie Wilson to record, since Wells knew of Gordy's collaboration with Wilson. However, a tired Gordy insisted Wells sing the song in front of him. Impressed, Gordy had Wells enter Detroit's United Sound Studios to record the single, titled "Bye Bye Baby". After a reported twenty-two takes, Gordy signed Wells to the Motown subsidiary of his expanding record label and released the song as a single in late 1960 where it eventually peaked at number eight on the R&B chart in 1961, later crossing over to the top fifty on the pop singles chart where it peaked at number 45.

Wells' early Motown career insisted on a rougher R&B production that predated the smoother sound of her bigger hit recordings. Wells became the first Motown female artist to have a top forty pop single after the Mickey Stevenson-penned doo-wop single, "I Don't Want to Take a Chance", hit number thirty-three. In the fall of 1961, Motown issued her first album and released a third single, the blues-styled ballad "Strange Love". However when that record bombed, Gordy set Wells up with The Miracles' lead singer Smokey Robinson. Though she was hailed as "the first lady of Motown", Wells was technically Motown's third female signed act: Claudette Rogers of Motown's first star group The Miracles, has been referred to by Berry Gordy as "the first lady of Motown Records" due to her being signed as a member of the group, and in late 1959 Detroit blues-gospel singer Mable John signed to the then-fledging label a year prior to Wells' arrival. Nevertheless, Wells' early hits as being one of the label's few female solo acts did make her the label's first female star and its first fully successful solo artist.

Wells' teaming with Robinson began a succession of hit singles the duo would collaborate on in the following two years. Their first collaboration, 1962's "The One Who Really Loves You", was Wells' first smash hit, peaking at number-two on the R&B chart and number-eight on the Hot 100. The song featured a calypso-styled soul production that defined Wells' early hits. Known for releasing songs with a repetitive sound, Motown released the similar-sounding "You Beat Me to the Punch" a few months later. The song became her first R&B number-one single and peaked at number nine on the pop chart. The success of "You Beat Me to the Punch" helped to make Wells the first Motown star to be nominated for a Grammy Award as the song was nominated in the Best Rhythm & Blues Recording category.

Then in late 1962, Motown released "Two Lovers". The single became Wells' third consecutive single to hit the top ten of Billboard's Hot 100 where it peaked at number-seven and became her second number-one hit on the R&B chart. This help to make Wells the first female solo artist to release three consecutive top ten singles on the pop chart. Wells' second album, also titled The One Who Really Loves You, was released in 1962 and peaked at number-eight on the pop albums chart, making the teenage singer a breakthrough star and giving her clout at Motown. Wells' success at the label was recognized when she became a headliner during the first string of Motortown Revue concerts, starting in the fall of 1962. The singer showcased a rawer stage presence that contrasted with her softer R&B recordings.

Wells' success continued in 1963 when she hit the top twenty with the doo-wop ballad "Laughing Boy" and scored three top forty singles that year including "Your Old Standby", "You Lost the Sweetest Boy", and its B-side "What's So Easy for Two Is So Hard for One". "You Lost the Sweetest Boy" was one of the first hit singles composed by the successful Motown songwriting and producing trio Holland-Dozier-Holland, though Robinson remained Wells' primary producer.

During that year, Wells recorded a session of successful B-sides that became as well-known as her hits, including "Operator", "What Love Has Joined Together", "Two Wrongs Don't Make a Right" and "Old Love (Let's Try It Again)". Wells and Robinson also recorded a duet together titled "I Want You 'Round", which would be re-recorded by Marvin Gaye and Kim Weston.

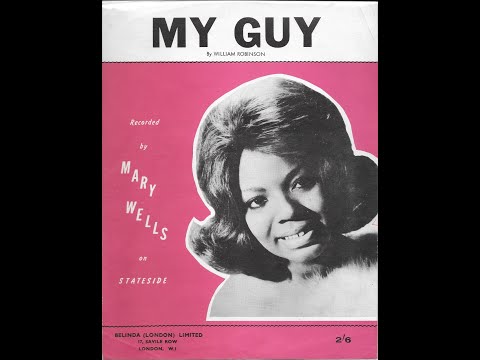

In 1964, Wells recorded and released "My Guy". The Smokey Robinson song became her trademark single, reaching number-one on the Cashbox R&B chart for seven weeks, becoming the number-one R&B single of the year. The song successfully crossed over to the Billboard Hot 100, where it eventually replaced Louis Armstrong's "Hello, Dolly!" to hit number-one on that chart where it stayed for two weeks. To build on the song's success, Motown released a duet album recorded with fellow Motown singing star Marvin Gaye, Together. The album peaked at number one on the R&B album chart and hit number forty-two on the pop album chart and yielded the double-sided hits "Once Upon a Time" and "What's the Matter With You Baby".

"My Guy" was one of the first Motown songs to break over the other side of the Atlantic, where it eventually peaked at number five on the UK chart, making Wells an international star that year. Around this time, despite competition, The Beatles publicly stated that Wells was their favorite American singer and soon she was given an invitation to open for the group during their tour of the United Kingdom, thus making her the first Motown star to perform in the UK. Wells was only one of three female singers to open for The Beatles, the other singers were Brenda Holloway and Jackie DeShannon. Wells made friends with all four Beatles and later released a tribute album, Love Songs to the Beatles in mid-decade.

When describing Wells' landmark success in 1964, former Motown sales chief Barney Ales:

"In 1964, Mary Wells was our big, big artist, I don't think there's any audience with an age of 30 through 50 that doesn't know the words to My Guy."

Ironically during her most successful year, Wells was having problems with Motown over her original recording contract, which she had signed at the age of seventeen. She was also reportedly angry that the money made from "My Guy" was being used to promote The Supremes, who were at last finding success with "Where Did Our Love Go". Though Gordy reportedly tried to renegotiate with Wells, the singer still asked to be let go of her contract with Motown.

A pending lawsuit would keep Wells away from the studio for several months, as she and Gordy went back and forth over the contract details, Wells fighting to gain larger royalties from earnings she had made during her tenure with Motown. Finally, she invoked a clause that allowed her to leave the label, telling the court that her original contract was invalid since she signed while she was still a minor. Wells won her lawsuit and was awarded a settlement, leaving Motown officially in early 1965, whereupon she accepted a lucrative ($500,000) contract with 20th Century Fox Records.

A weary Wells worked on material with her new record label while dealing with other issues, including being bed-ridden for weeks suffering from tuberculosis. Wells' eponymous first 20th Century Fox release featured the modest hits "Ain't It The Truth", the B-side "Stop Taking Me for Granted", the lone top 40 hit, "Use Your Head" and "Never, Never Leave Me". However, the album flopped as did the Beatles tribute album she released not too long afterwards. Rumors have hinted Motown may have threatened to sue radio stations for playing Wells' post-Motown music during this time. After a tenuous and stressful period in which Wells and the label battled over creative differences and withdrawal after Wells' records failed to chart successfully, the singer asked to be let go in 1965 and left with a small settlement.

Wells' film career never truly panned out only having one bit part in the 1967 film, "Catalina Caper". In 1966, Wells signed with the Atlantic Records subsidiary Atco. Working with producer Carl Davis, Wells scored her final top ten R&B hit with "Dear Lover", which also became a modestly successful pop hit, peaking at number fifty-one. However, much like her tenure with 20th Century Fox, the singer struggled to come up with a follow-up hit and in 1968 she left the label for Jubilee Records, where she scored her final pop hit, "The Doctor", a song she co-wrote with then-husband Cecil Womack, of the famed Womack family. Two years later Wells left the label for a short deal with Warner Music subsidiary Reprise Records and released two Bobby Womack-produced singles before deciding to retire from music altogether in 1974 to raise her family.

In 1977, Wells divorced Cecil Womack and returned to performing on the road in 1979. Performing in venues, she was spotted by CBS Urban president Larkin Arnold in 1981 and offered a contract with the CBS subsidiary, Epic Records. Wells accepted the contract and ended her seven-year retirement with the release of In and Out of Love, in October 1981. The album sparked a luke-warm career rebirth but yielded Wells' biggest hit in years, the funky disco single, "Gigolo".

The song became a smash at dance clubs across the country, which took the song's 12-minute-long mix to number thirteen on Billboard's Hot Dance/Club Singles chart, and number-two on the Hot Disco Songs chart. An edited three-minute version for radio was released to R&B stations in January, 1982, which helped the song achieve a modest showing at number 69. It turned out to be Wells' final chart single.

After the parent album failed to chart and/or release concurrent follow-ups, the Motown-styled "These Arms" was released, but it was quickly withdrawn after the album tanked and Wells' Epic contract fizzled out. The album's major failure was due to a light promotion but she had completed it in 1979 and it was withheld for two years; most likely due to financial and business logistics, with contributions in part by Wells' own personal problems. She still had one more album in her CBS contract and in 1982, she released an album of cover songs, Easy Touch, which featured a more adult contemporary flavor.

Leaving CBS in 1983, she continued recording for smaller labels, gaining new success as a touring performer. In 1989, she was celebrated with a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation during its inaugural year.

In the same year, 1990, Wells recorded an album for Ian Levine's Motorcity Records, Wells' voice began to cut off, causing the singer to visit a local hospital. Doctors diagnosed Wells with laryngeal cancer. Treatments for the disease ravaged her voice, forcing her to quit her music career. Since she had no health insurance, her illness wiped out her finances, forcing her to sell her home. Struggling to continue treatment, her old Motown friends -- including Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, members of The Temptations and Martha Reeves -- personally made donations to support her, along with the help of admirers such as Dionne Warwick, Rod Stewart, Bruce Springsteen, Aretha Franklin and Bonnie Raitt. The same year, a benefit concert was held by fellow fan and Detroit R&B singer Anita Baker. Wells was also given a tribute by friends such as Stevie Wonder and Little Richard on The Joan Rivers Show.

The following year, Mary Wells brought a multi-million dollar lawsuit against Motown for royalties she felt she had not received upon leaving Motown Records in 1964. It was also for loss of royalties for not promoting her songs like they should have. Motown eventually settled the lawsuit by giving her a six-figure sum. That same year, she testified before the United States Congress to encourage government funding for cancer research:

"I'm here today to urge you to keep the faith. I can't cheer you on with all my voice, but I can encourage, and I pray to motivate you with all my heart and soul and whispers."

In the summer of 1992, Wells' cancer returned and she was rushed to the Kenneth Norris Jr. Cancer Hospital in Los Angeles with pneumonia. With the effects of her unsuccessful treatments and a weakened immune system, Wells died on July 26, 1992 at the age of forty-nine. After her funeral, which included a eulogy given by her old friend and former collaborator Smokey Robinson, Wells was laid to rest. She is buried in Glendale's Forest Lawn Memorial Park.

Though Wells has been eligible for induction to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame - she was nominated twice in 1986 and 1987, she has yet to achieve it. Wells earned one Grammy Award nomination during her career and in 1999, the Grammy committee inducted Wells' "My Guy" to the Grammy Hall of Fame assuring the song's importance. Wells was given one of the first Pioneer Awards by the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1989. A year later, the foundation raised more than $50,000 to help with Wells' treatment after her illness had wiped out all of her finances. In 2006, she was inducted to the Michigan Rock & Roll Legends Hall of Fame.

Wells married twice. In 1960, she married Detroit singer Herman Griffin. The marriage of the teenage couple was troubled from the start due to their age and Griffin's unhealthy control of Wells. They divorced in 1963. Despite rumors, Wells never dated fellow Motown singer Marvin Gaye, who would go on to have successful duet partnerships with Kim Weston, Tammi Terrell and Diana Ross after Wells left Motown. In 1966, Wells married singer-songwriter Cecil Womack, formerly of The Valentinos and the younger brother of music legend Bobby Womack. The marriage lasted until 1977 and resulted in three children. Wells began an affair with another Womack brother, Curtis, in 1979. Like her marriage to Griffin, her relationships with the Womack brothers were reportedly abusive. Wells was a notorious chain smoker and went through bouts of depression during her relationships. By the time she left Curtis Womack in 1990, Wells had developed a heroin habit. After her split from Curtis, Wells was able to beat her heroin habit, and focused on raising her youngest daughter until her cancer appeared. Mary had four children: sons Cecil, Jr. and Harry, and daughters Stacy and Sugar

Read more on Last.fm. User-contributed text is available under the Creative Commons By-SA License; additional terms may apply.